|

ditching aircraft

The majority of aeroplanes are not designed for ditching!

However, having said that, the statistical chances of

surviving a ditching are high. It is estimated from UK and USA data that 88% of

controlled ditchings result in few injuries to pilots or passengers.

You are more likely to die after ditching by drowning,

usually hastened by hypothermia and exhaustion. By wearing a life jacket in the

aeroplane your survival prospects are greatly improved. However in cold water,

15 degrees Celsius or less, your life expectancy in the water is only about one

hour.

If one has to ditch what are the issues?

In general terms it is always preferable to impact the water

as slowly as possible, under full control; don't stall the aeroplane in. Keep

the wings parallel with the surface of the water on impact, i.e. wings level in

calm conditions. One wing tip striking the water first will cause a violent

uncontrollable slewing action.

In ideal conditions you should always ditch into wind because

it provides the lowest speed over the water and therefore causes the lowest

impact damage. This process is effective provided the surface of the water is

flat or if the water is smooth with a very long swell inside which the aeroplane

will come to rest.

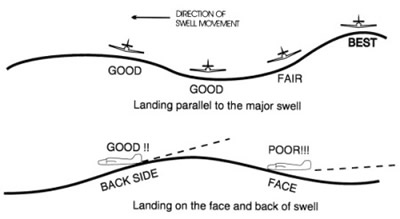

If the swell is more severe, including breaking waves, it is

more advisable to ditch along the swell, accepting the cross wind and higher

speed over the water, because this is preferable to ditching into the face of a

wave and nosing in. Ditching into the face of a wave is very likely to cause

extreme damage to the aeroplane and violent deceleration with severe

implications for passengers and crew. The final approach will result in

considerable drift which you must control to achieve the required tracking over

the water. You must be careful to maintain sufficient airspeed to ensure that

any action you take in controlling the path of the aeroplane does not lead to a

stall. You must retain complete control of the aeroplane.

In extremely windy conditions, greater than 20 knots for

light aeroplanes with low stalling speeds or 30 knots or more for heavy

aeroplanes with high stalling speeds, it may be worth ditching into wind to gain

the large reduction in speed over the water. Aim to touchdown on the receding

face of the swell. You may need to compromise between the beneficial effects of

wind and the problems of swell. Advice on judging wind speed is provided at the

end of this article.

In many cases, especially for modern or the more complex

aeroplanes, the aircraft flight manual (or pilot's operating handbook) will

provide detailed handling information for the execution of a ditching. In the

absence of such information you should consider the following:

• Don life jacket if time permits;

• Reduce the aeroplane's weight to a minimum if you have time

and if practicable. This will reduce the stalling speed and therefore your

planned impact speed;

• Ensure landing gear is up and the associated circuit

breaker pulled;

• Dispose of, or restrain, any loose articles in the cabin

which could create a hazard during impact;

• Consider possible airframe distortion on impact and arrange

to have an escape door or hatch open before impact so that you can vacate the

aeroplane;

• Make every effort to precisely control airspeed and rate of

descent, both should be as low as possible, consistent with maintaining full

control of the aeroplane. If you are conducting a glide approach you must

consider approaching at a higher speed which will provide the lift energy

necessary for the larger than usual round-out to reduce the rate of descent at

impact to one which is appropriate;

• Ditch into wind if possible otherwise ditch along the swell

(see above), a compromise may be necessary in extreme cases;

• Use flaps set to a medium position to ensure the slowest

speed on impact; flaps also usually induce a lower angle of incidence and

therefore smaller aeroplane body angle when approaching stalling speed thus

providing for a better aeroplane attitude on impact;

• If possible make the approach using power. If the ditching

has to occur because of impending fuel exhaustion make the approach before all

the fuel is expended. A powered approach provides for the greatest potential to

execute a successful round-out and hold off enabling the aeroplane to have

almost no descent rate at impact;

•Be

prepared for a violent impact, there will probably be two or more impacts, the

tail end of the aeroplane followed by the entire fuselage.

At night the use of lights could be critical. You should set

the cockpit lights as low as possible to optimise your night vision and

carefully consider the use of landing lights or possibly taxi lights. The very

directional nature of landing lights could cause confusion for the pilot,

whereas the more general light provided by taxi lights may prove more

satisfactory. If the air is misty (a serious probability if there is blowing

spray), the glare of external lights could upset your night vision and prove

more of a hindrance than a help.

One of the most difficult things to get right in a ditching

is judging the height for the round-out and hold-off. Most people will not have

experienced many landings without an undercarriage. Thus you will be used to

seeing a particular attitude at the round-out. In the ditching case that

attitude will be a little different because the aeroplane should be a little bit

closer to the surface to cater for the lack of an undercarriage. You will need

to make some allowance for that. This is where a powered approach can be most

beneficial because you can use power to control that final descent onto the

water. Of course if you fly an aeroplane with a fixed undercarriage you have

another problem which we will consider later.

Judging height over water can be extremely difficult

particularly when the water is calm or on a very dark night. An aneroid

altimeter will be of little use unless you have an accurate QNH. The best device

to use is a radio/radar altimeter if you have one. If all else fails set up a

low rate of descent, less than 200 feet a minute and wait. This is another good

reason for conducting a powered approach if power is available.

Behaviour of the aeroplane on impact

The overall design of an aeroplane has a significant

influence on how it will behave during the ditching impact. As a general rule,

aeroplanes with an almost straight fuselage under surface will behave in a more

benign manner than ones with a swept up rear fuselage. Because of the angle of

attack of the wings near the stall, all aeroplanes have a nose high tail low

attitude near the stall and therefore, if flown correctly, will have such

an attitude as they impact the water. Thus the rear fuselage will impact the

water first, except for fixed undercarriage aeroplanes. If the rear fuselage is

markedly upswept it is not unusual immediately after impact for the aeroplane to

violently pitch up to an almost vertical attitude before violently crashing down

onto the surface and probably nosing under the water.

Aeroplanes with straight under surfaces are less likely to

suffer such a violent pitch up and subsequent violent pitch down.

The use of moderate flap also has an effect as mentioned

above, both reducing touch down speed and aircraft body angle.

Ditching into the face of the swell or into waves should be

avoided because the aeroplane will behave in a similar manner to one impacting a

cliff face.

Aeroplanes with fixed undercarriages strike the water wheels

first. This is most likely to cause violent nose down pitch with the aeroplane

ending up in a near vertical position with the nose buried under the water.

Individual aeroplane design may have a significant effect on this outcome with

aeroplanes with a significant amount of their structure ahead of the main wheels

performing in a less violent manner. Aeroplanes with retractable undercarriages

should always be ditched with the gear retracted unless the flight manual

specifically instructs otherwise.

After the aeroplane has come to rest, high wing aeroplanes

may quickly assume an attitude where most of their fuselage, and therefore you,

is under water. Low wing aeroplanes are more likely to keep the fuselage above

water. How long either type stays in that position before sinking is related to

many issues. It is best to assume that you will have little time, so evacuate

the aeroplane quickly but in an orderly and organised manner. This is best

achieved if all the passengers and crew have been comprehensively briefed during

the descent phase prior to impact so that everyone knows what they have to do

and what their responsibilities are.

|

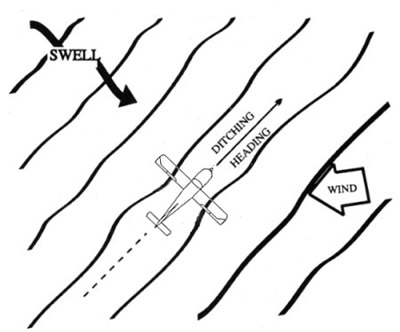

Single Swell (15 knot wind) |

|

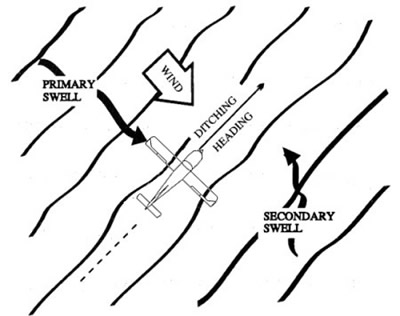

Double Swell (15 knot wind) |

|

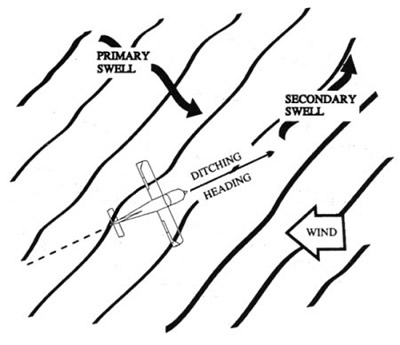

Double Swell (30 knot wind) |

|

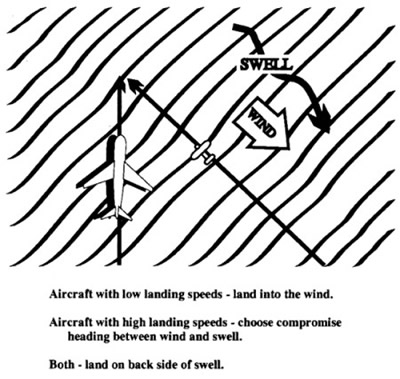

(50 knot wind) |

|

Wind-Swell-Ditch Heading |

Escape from the aeroplane

You have survived the impact now to leave the aeroplane

before it sinks.

Before we begin it may be worth considering how we might best

protect ourselves from the worst effects of the ditching impact. Obviously we

should be well strapped in, if possible using upper body restraint. Even in this

situation our head and legs are not well restrained and are prone to damage with

obvious results. Consideration should be given to protecting the head and legs

by adopting the crash position. Restraining head and leg movement during impact

should be considered. The issue of body protection during severe impact

situations is a large and complex subject which will only be covered in this

article at a superficial level.

Now to leave the aeroplane. As has already been mentioned, it

is best to have a door or hatch wedged open before impact because airframe

distortion may make it difficult if not impossible to open the door after

impact. However, ingress of water during the impact should also be considered

but normally have at least one door or hatch open.

If you have not been wearing your life jacket make sure you

collect it before you leave and put it on as soon as possible. Do not inflate it

inside the aeroplane; it will almost certainly seriously impede your exit.

Collect and deploy life rafts if you have them. Collect all signalling equipment

and survival gear you have, ideally it should all be combined in one or more

convenient packs or included in your life jacket or life raft.

At night it will be advisable to have the cabin lights on.

Survival aspects of ditching

If you have any influence on where you are going to ditch

consider making ease of rescue an issue. Thus if possible ditch near a benign

shoreline if you can't land on solid earth. Ditching near a treacherous

shoreline on the other hand should be avoided. Seek out shipping if any are

within range and try to ensure that they see you. Ditch in the front hemisphere

of the ship though not directly inline with its track!

Strap in tightly, protect head and legs to the best of your

ability. Use pillows, blanket rolls or soft baggage as devices to restrain

excessive and violent movement of your extremities. If you intend to use a life

raft it will be advisable to consider your footwear. Soft shoes and ones with

rubber or other soft soles and heels should be satisfactory but high heel shoes

and ones with hard and angular soles and heels should be discarded. If you are

likely to have to swim discard your shoes.

The overall issues related to survival in order of importance

are:

•

Protection;

• Location;

• Water;

• Food.

Checklist

Before long over-water flights review your plans for ditching

and subsequent survival, and establish what rescue services are available and

how you can optimise their usefulness.

The following suggested coverall check list is provided for

your consideration, it is not designed for your aeroplane or your operation, you

must make your own check list considering the issues raised above and the

information provided in this check list.

• Plan to ditch using power if you have a choice;

• Look for likely rescue sources . ships, shorelines;

• Make Mayday calls, set transponder to 7700;

• Study the wind and sea surface; make a plan of action for

the direction of the ditching manoeuvre;

• Burn off or jettison fuel if possible, ensure aeroplane is

as light as practicable;

• Jettison any freight and other unnecessary heavy objects;

• Brief all crew and passengers, covering their actions and

responsibilities before and after the ditching event including the use of a life

jacket;

• Ensure all survival equipment is readily accessible,

including your personal locator beacon;

• Ensure there are no loose objects anywhere in the cockpit

or cabin;

• Conduct pre-landing checks, leave undercarriage up unless

it is advised to do otherwise;

• Select an intermediate amount of flap to optimise lift but

not providing high drag, unless advised otherwise;

• Wedge open some doors or hatches;

• Make a final decision on the direction of ditching;

• Set up the final approach not below 500 feet above the

surface;

• If you can accurately judge the height of the aeroplane

above the water, round out at the usual round-out height and hold off until

impact, ensure rate of descent is less than 200 feet a minute and wings parallel

with the sea surface, level for a calm surface;

• After the aeroplane stops, vacate, taking all necessary

gear;

• Don't inflate life jacket inside the aeroplane.

Ongoing survival considerations

It is no good surviving for a time if

you cannot be found or no one is looking for you, so ensure

that you have a good personal locator beacon, preferably one

that communicates via a satellite, and that someone will miss

you when you don't arrive. Consider activating a locator

beacon before impacting the water.

Survival is a complex issue. Statistics

tell us that only 50% of those that survive the ditching

survive to be rescued. You are advised to seek out specialised

training appropriate to your operation and the climatic

conditions you operate in. What follows are some general

guidelines which in no way can substitute for proper training.

After leaving the aeroplane, survival

is the only issue to consider until rescue arrives. But to

give you the best chance of rejoining civilization you should

have already made a number of important decisions.

Plan for the Worst. The first

decision is to accept that .it could happen to me.. This means

you should be prepared, taking into account the probabilities

Single engine aeroplanes are more

likely to ditch than twin engine aeroplanes. Approved single

engine aeroplanes are most unlikely to ditch. However, any

aeroplane can find itself in a situation where the only option

is to ditch.

Another variable to consider is the

time factor; how long are you flying over water. Crossing a

river is usually going to represent less risk than crossing

the Pacific Ocean, all things being equal.

How should you prepare? First ensure

that air traffic services know you exist and carry your SAR

details, and take at least one personal locator beacon on your

flight.

Ensure that you have enough appropriate

life jackets for everyone and possibly a spare or two. Notice

the word .appropriate.. A life jacket not designed for use in

an aeroplane is not appropriate. An airline life jacket will

also not be appropriate in many aerial work or private

operations where the jacket should be worn regularly. If you

are in doubt about which sort of life jacket to use discuss

the matter with an aviation safety equipment supplier or

servicing agent. Your life jacket should be equipped with at

least a whistle and a light. Calling out is much more

difficult than blowing a whistle when you are trying to

attract someone's attention and a light or strobe is

invaluable at night.

Ongoing survival considerations

If the water is cold or you are flying

far away from sources of rescue you would be advised to carry

sufficient life rafts to cater for everybody. You may also

consider using enhanced body protection such as immersion

suits in extreme conditions of cold. Out of the water woollen

clothes retain 50% of their insulating qualities when wet as

opposed to cotton, which retains 10%. In the water only

specialised clothing is likely to provide significant

protection. In or out of the water, any form of hat or head

covering should be used, you lose a great amount of heat from

your exposed head, even a plastic bag will help keep your head

warm. Consider first aid too:

- Start the breathing;

- Stop the bleeding;

- Protect the wound;

- Immobilise the fracture;

- Treat for shock.

If this means little to you consider

getting some first aid training.

Survive

You have lived

through the ditching now you have to survive until you are

rescued.

If possible always wear your life

jacket in the aeroplane, it will prove very difficult to put

on in the confined space after you have suffered an emergency.

If wearing the jacket is not practical be sure you know where

it is and how to get it without delay. >Do not inflate the

life jacket inside the aeroplane

Collect any other survival and signalling equipment you have

provided for yourself and leave the aeroplane. Once outside

inflate the life jacket as soon as possible.

If you do not have a life raft enter

the water and move away from the aeroplane, attempt to keep

close to other people and assist them as best as you can. Make

every effort to keep together including connecting each other

together by a line should you have one. Aeroplane tie down

ropes would be most useful in such circumstances. Ensure you

attach your survival and signalling equipment to yourself.

If you have a life raft attach it to the

aeroplane by a line and deploy it. In high winds and rough

water it will be very easy to lose your life raft as it

deploys and literally blows away. Enter the raft ensuring that

your footwear and other items of apparel do not represent a

risk to the delicate fabric of the life raft. Take all your

survival equipment with you and any other articles which could

be of use. Blankets, warm clothes, rope and the like, but also

consider the weight of this equipment and the buoyancy of your

life raft.

Once everyone is on board together

with your selected equipment, detach the life raft from the

aeroplane and move clear. Obviously, at any time, should the

aeroplane start to sink, immediately detach the life raft.

Ensure the raft'.s sea anchor is deployed as soon as practical,

inflate the floor and erect the canopy to provide added

protection. Attach at least one person to the raft just in

case it overturns. It will make re-boarding easier. Bail out

the water and use the sponge provided to dry the inside of the

raft. Ensure the buoyancy chambers are fully inflated, a hand

pump is provided for the purpose. The chambers should be firm

but not rigid, do not over inflate.

Activate any emergency locator

equipment (one personal locator beacon at a time unless you

become separated) and make yourselves as comfortable as

possible. Consider how long you expect to wait until search

and rescue arrives and make plans accordingly. With a group of

people it is advisable to instigate a shift system to keep a

lookout for searching aircraft and shipping. There should be

somebody performing this essential task at all times of day

and night.

Sort out your signalling equipment to

ensure that it is readily available should a search aircraft

or passing ship arrive in your area. You should educate

yourself on how to use the equipment and in the case of

devices such a heliographs practise using them. Remember that

in the wide expanse of the ocean an individual or even a life

raft is extremely difficult to find. There can be few more

depressing feelings than being missed by a searching aircraft,

so help the searcher all you can.

Make every effort not to become

seasick; vomiting will advance the adverse effects of

dehydration. Seasickness tablets may be a useful item for your

survival pack. Keeping your body adequately hydrated is always

an important physiological aspect of survival.

If you do not have a life raft and find

yourself alone in a vast expanse of water,

do not give up hope. Your will to survive is

the most powerful force to prolong your life In cold water your largest threat is

losing body heat. As quickly as possible perform any manual

tasks before your hands become too cold to function properly.

Ensure your personal locator beacon is activated and if

possible attach it to your life jacket, with the aerial as

vertical as possible. Keep as warm as you can by adopting the

Heat Escaping Lessening Position (HELP). Hold the inner sides

of your arms against the sides of your chest and fold you arms

in front of you to keep the cold water from freely circulating

all around your arms. Hold your thighs together and raise them

slightly to protect the groin, again with the objective of

reducing water circulation around critical parts of the body.

If you are with others huddle together

in small groups of three or four with the sides of your chests

and lower bodies pressed close together. Place children in the

middle of the huddle. In all cases do not swim to retain body

heat, such exercise and associated blood flow will only

accelerate the heat loss process. If you are a strong swimmer

you may consider swimming to a shore but only if it is 1

kms. Otherwise wait for rescue unless none will be coming

because no one knows about you or your predicament.

Even if you do not have a life jacket,

do not give

up hope

Cushions, plastic bottles, boxes, polystyrene pieces, even

plastic bags inflated like a balloon can help.

Rescue

If survival equipment is dropped to you use

it. It will often consist of two or more attached packs. Climb

on board the life raft and investigate what equipment has been

provided for you and use it as instructed.

8.2 When rescue arrives do not stop

signalling until you are certain they have you in contact.

Then stop signalling. Then:

Remain seated, do

not stand up;

Wait for them to initiate the rescue, do not do

anything on your own initiative;

If a helicopter is making a winching rescue, do

nothing until instructed by the winch man, do not reach out

for the cable;

Do as you are instructed, they are the experts.

Conclusion

Most accidents are preventable with

forethought and competent operation. All accidents are made

more survivable with forethought and competent action.

Make sure you plan your flight

carefully and recheck your calculations, better still get

someone else to recheck your rechecked calculations. Ensure

your aeroplane is fully maintained and that you trust the

person doing that maintenance. Always plan for the worst case

and add a buffer particularly in the quantity of fuel you plan

to uplift. Fuel in the tanker will do you no good! CAAP 234-1

provides good guidance about the minimum fuel you should

carry, but remember that the variable fuel requirement only

caters for 10% to 15% error in wind effect on your flight. Are

you prepared to bet your life on a met forecast?

If you have to ditch, use your

pre-planned checklist and do what it says.

Employ the survival advice you have

gained from previous training.

Plan and prepare for the worst, you are

worth it!

| Wind Speed

|

Appearance of Sea

|

Effect on

Ditching |

| 0-6 knots

|

Glassy calm to small

ripples |

Height very

difficult to judge above glassy surface. Ditch parallel to swell

|

| 7-10 knots

|

Small waves; few if

any white caps |

Ditch parallel to

swell |

| 11-21 knots

|

Larger waves with

many white caps |

Use headwind

component but still ditch along general line of swell |

|

22-33 knots

|

Medium to large

waves, some foam crests, numerous white caps |

Ditch into wind on

crest or downslope of swell |

| 34 knots and above

|

Large waves, streaks

of foam, wave crests forming spindrift |

Ditch into wind on

crest or downslope of swell. Avoid at all costs ditching into face of rising

swell |

Note: The effects on ditching mentioned in

the table are appropriate for light aeroplanes only.

Power-off Ditching:

- RADIO--TRANSMIT MAYDAY on 121.5 MHz or any other frequency, if able,

giving location and intentions.

- WING FLAPS--AS DESIRED (Flaps up recommended).

- APPROACH--INTO THE WIND. Except in light winds and heavy swells, in which

case LAND PARALLEL TO SWELLS.

- HARNESS--SECURE. Brief passengers without shoulder harness to remove

eyeglasses and cushion face with folded coat or blanket just prior to

touchdown. Don life vests if practical. Do not inflate prior to egress.

- CABIN DOORS--UNLATCH AND LOCK OPEN.

- AIRSPEED--80 KIAS (Flaps up). 70 KIAS (Flaps down).

- TOUCHDOWN--TWO STEP FLARE WITH TOUCHDOWN AT MINIMUM AIRSPEED. Keep wings

parallel to water if landing along swells. If able, kick drift off with rudder

prior to touchdown.

- AIRPLANE--EVACUATE through any available exit. If necessary, open window

and flood cabin to equalize pressure so doors can be opened.

- LIFE VESTS AND RAFT--INFLATE AFTER EGRESS.

NOTE

Expect one or more preliminary light skips before the

principal impact with the water. The principal water im pact may be severe. Do

not unfasten the harness too early. Do not inflate the flotation gear prior to

exiting the airplane. Under some light wind conditions, glassy water may make

judging the height above water surface very difficult. The above procedure is

generally the best way to make a water landing without power. In glassy water

situations, make every effort to use other cues, such as floating objects or

shorelines, to judge height above water.

Power-on Ditching:

- RADIO--TRANSMIT MAYDAY on 121.5 MHz or any other frequency, if able,

giving location and intentions.

- HEAVY OBJECTS--SECURE OR JETTISON, if practical.

- WING FLAPS--AS DESIRED (Flaps down recommended).

- APPROACH--INTO THE WIND. Except in light winds and heavy swells, then LAND

PARALLEL TO SWELLS.

- HARNESS--SECURE. Brief passengers without shoulder harness to remove

eyeglasses and cushion face with folded coat or blanket just prior to

touchdown. Don life vests. Do not inflate prior to egress.

- CABIN DOORS--UNLATCH AND LOCK OPEN.

- AIRSPEED--60 KIAS (Flaps down).

- TOUCHDOWN--USE POWER TO ESTABLISH 100 - 200 FT/MIN DESCENT AT 60 KIAS.

Keep wings parallel to water if landing along swells. If able, kick drift off

with rudder prior to touchdown.

- AIRPLANE--EVACUATE through any available exit. If necessary, open window

and flood cabin to equalize pressure so doors can be opened.

- LIFE VESTS AND RAFT--INFLATE AFTER EGRESS.

NOTE

Expect one or more preliminary light skips before the

principal impact with the water. The principal water impact may be severe. Do

not unfasten the harness too early. Do not inflate the flotation gear prior to

exiting the airplane. The touchdown technique is a no-flare power touchdown.

Glassy water may make judging the height above the water surface very difficult.

With power available, do not attempt to guess the point at which to flare, but

allow the airplane to fly itself into the water at minimum safe speed with

sufficient power to keep descent rate at a safe level.

|