Note the

power lines on the ridge

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

statistics for any particular year during the past two decades include a

list of the most frequent causal factors for

general aviation accidents.

The troubling point of these statistics is

that the same things are causing the same accidents year after year. This

points out the need for continued refresher training to establish a higher

level of flight proficiency for all pilots.

Doesn’t this remind you of the saying, “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on

me.” It should bother us that we, as pilots, are unable to

learn from the mistakes of others.

The first item on the NTSB’s top ten

list is “inadequate pre-flight preparation and/or

planning,” that denotes we must spend time thinking about the

flight.

Will the

flight extend into the night? Do I need a flashlight? Is the

destination airport lighted? Are services available at my time of

arrival?

What if I

run into a venturi effect over the mountains? Will I have enough

fuel to continue the flight to the destination?

Suppose

un-forecast weather crops up, where will I go? What will I

do?

These examples show that pre-flight planning

is not just a matter of digging out the plotter and computer.

The next item on the NTSB list is

“landing accidents—excessive speed on the landing roll or failure

to correct for crosswind conditions.”

The third item is “continued VFR

flight into adverse weather conditions.” Each year some 200

accidents are listed under this category. The really sad part about this

is about 65 percent of these accidents are fatal.

How do these accidents occur when everyone

knows that pushing the weather on a VFR flight is not wise?

Is it that the pilot cannot recognize

“adverse weather conditions” from a distance and unintentionally gets in

the weather? Most times intentional scud running is the main

culprit. Those scattered clouds that are easily flown around in open

country can be a menace in a narrow canyon. Yet pilots continue to scud

run. And, not all of them are low-time pilots who haven’t learned better.

Some are high-time pilots—maybe instrument-rated—and mostly of sound

judgment.

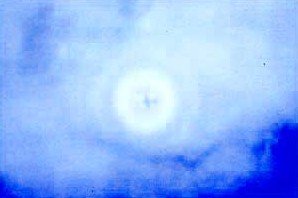

Flying above a layer of clouds

with the sun at your back will produce a "glory" if the cloud is composed

of liquid water. This rainbow circle is caused by a diffraction

phenomenon. Beware of icing in these clouds if the outside air temperature

is near freezing or below freezing.

Often the aircraft's shadow is

visible in the centre of the "glory" rainbow ring.

Some pilots scud run successfully, having

found it necessary to do so from time to time because of ice or turbulence

aloft, strong headwinds at IFR altitudes, navigation equipment failures,

or flying to a destination that does not have an instrument approach

facility.

Whatever the reason, they do it. But, they have disciplined

themselves and learned how to scud run safely.

Experienced pilots develop rules that

they will not deviate from under any circumstances.

Minimum

weather: 2,000-foot ceiling and 5 miles visibility. If weather

reports of five miles visibility or better do not exist at stations

beyond the destination, don’t

go.

Do not scud

run a route you have not previously flown at 1,500 feet AGL or less.

Even so, the terrain looks much different when the weather is

bad.

Do not scud

run toward worsening weather. The tendency to push on for a few more

miles is just too great.

scary practice

One frightening pilot technique unconsciously

practiced by many pilots when the weather is marginal is that of flying

near the cloud base. This is a natural tendency since it places the

airplane farther away from the ground. But, you have to realize the

forward visibility will be severely limited near the cloud base, allowing

you to fly into trouble before you can see it.

An experienced pilot will fly low.

Divide

the area from the ground to the cloud base into thirds and fly the middle

or lower third. If terrain constraints prohibit this, don’t

fly.

rules

Keep

navigation simple by following a highway or railroad. Pay attention

to your chart to make sure there isn’t a tunnel. Be cautious about

following a river. That’s where the poorest visibilities tend to

gather.

Turn on all

your lights. It’s not likely that anyone else will be out there with

you, but if they are, you want them to see and avoid your airplane.

When flying through a narrow canyon like The Gorge between Portland

and The Dalles, Ore., it is customary to remain to the right side,

just as on a highway, to avoid pilots going the other

way.

Throttle

back to a comfortable slow-speed cruise to keep the terrain features

clearly in

sight.